|

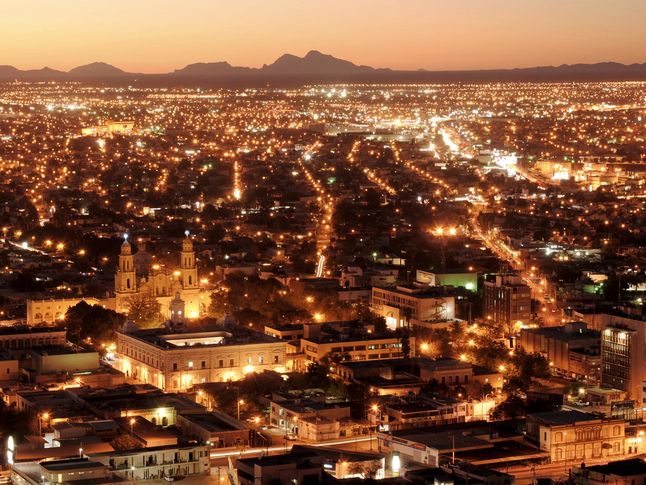

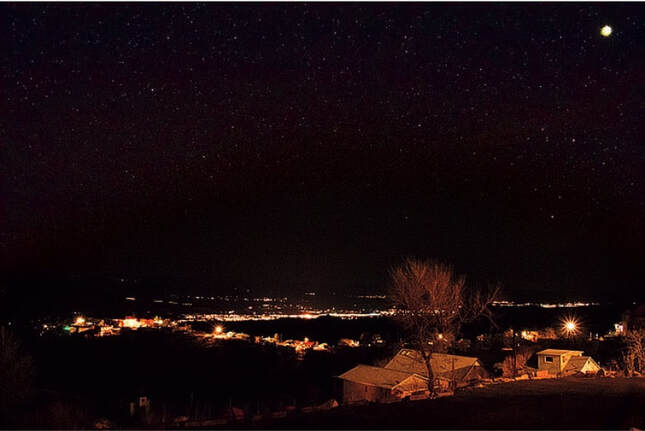

International Dark-Sky Association John C. Barentine, Ph.D. Director of Public Policy Amanda Gormley Director of Communication December 17, 2019 The Senate of Mexico unanimously endorsed legislation that classifies light pollution as a form of environmental pollution this November. The new law makes light pollution subject to regulation under existing environmental laws in the country of Mexico. The bill, called “Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la ley general del equilibrio ecológico y la protección al ambiente” (“Decree for the reform and addition of various provisions of the general law of ecological balance and the protection of the environment”), was approved by the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of the Mexican Congress) and is now set to become the official policy of Mexico. This legislation is an historic event worldwide because it is the first instance of a country explicitly defining light pollution as an environmental pollutant. The law is also unique because it amends previously existing environmental legislation that regulates air, water, and soil quality to also set regulations for light pollution. The law amends and expands the General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection of 1988 (LGEEPA). It gives regulatory authority of light pollution to the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), in coordination with the Ministry of Energy (SENER). The law tasks these ministries with “the prevention of environmental pollution caused by intrusive light.” “It took more than three years of hard work, but we did it,” said Fernando Ávila Castro, the leader of IDA Mexico and a member of the technical staff of the Institute for Astronomy at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Ensenada. The Institute’s “Oficina de la Ley del Cielo” (“Office of the Law of the Skies”) worked behind the scenes. Together with Former Chamber of Deputies member Tania Arguijo, Dr. José Franco, Zeus Valtierra, and Enrique Azures, the team influenced the lawmaking process for the benefit of protecting night skies across Mexico. The detailed regulations will be incumbent on regional and local governments throughout Mexico, as well as on both public and private property owners. According to the Senate opinion, the law is intended “to encourage the implementation of an adequate policy to reduce light pollution and the recovery of the clarity of the [night] sky, which entails a significant reduction of up to 50% of the expenditure to produce the electricity supplied by public lighting, based on the regulation of the use of suitable luminaires.” The new framework for regulating light pollution enables the creation of special areas where lighting limits are the most strict, such as astronomical observatories, archaeological ruins, national parks, and nature reserves. The protection of their night skies — among the darkest in Mexico — “can only be ensured through the proper application of Mexican federal laws,” said Ávila Castro. Since LGEEPA already involves requirements that local governments in Mexico must follow, a mechanism for implementing the new law already exists. “With these enabling legislation in place, SEMARNAT will be able to enforce them, even from the beginning of the design stage of any project,” Ávila Castro explained. “A new tourist development for example? It will have to comply with these new norms or it won’t have a building permit.” The Oficina de la Ley del Cielo is already in dialogue with the Environmental and Energy Ministries to establish the specific regulations called for in the new law, including illumination levels and limits on the correlated color temperature of light sources. Ávila Castro estimates that this process will take between one and two years to complete. To read more about this law, visit the announcement at the Senado de la República de México. IDA congratulates the hard work of our Chapter leader, Fernando Ávila Castro, and the country of Mexico for its historical and progressive law on light pollution. The City of Cottonwood has become the newest addition to the International Dark Sky Places Program, as an International Dark Sky Community. In an effort to continue to promote and protect our dark skies, it has been a mission of the City to obtain this designation since 2016. Working with the community as a whole, the City of Cottonwood has become the 23rd designated dark sky community in the world. The State of Arizona now accounts for 6 of those dark sky communities, with 4 of the 6 communities located in the Verde Valley. Light pollution affects the world as a whole, not only does it disrupt the natural day-night pattern but it also has negative impacts on the ecosystem, wildlife, and human health. Committing to being a dark sky community not only benefits the City but the surrounding community. As part of Yavapai County, buildings in Cottonwood are required to ensure that outdoor lighting is compliant with dark-skies ordinances, aimed at reducing light pollution and keeping the stars visible at night. Like many communities in the county, Cottonwood has gone beyond Yavapai’s regulations to encourage even more stargazer-friendly lighting; at a city council meeting on Oct. 2, 2018 Cottonwood amended its dark-sky ordinance with stricter rules. Cottonwood sought to become the next community in the Verde Valley to become recognized as an International Dark-Sky Community by the International Dark-Sky Association. “I think a lot of people are drawn to Cottonwood because of the natural beauty that we have surrounding us, and a big part of that is a sky where you can see the stars at night,” Cottonwood Mayor Tim Elinski said. “When you come down to the city of Phoenix or any large municipal area and see the glow on the horizon, it’s not always a welcoming sign. The more we can do to keep our skies dark the more attractive the community will be. I think preserving that for the future is an important thing to do.” The amended regulations are mostly the same as they were before in regard to private lighting, with the main addition being requirements for low-temperature ratings for outdoor lights, not exceeding 3000 lumens. Beyond that, the regulations continue Cottonwood’s rules for shielded lights of limited brightness facing downwards to prevent light pollution. “To say that there’s going to be a big effect on residential community — it’s not at all,” Cottonwood Code Enforcement Coordinator Christina Anderson said of the changes. “Almost every single commercial property within the city limits has changed their lighting, their signage, all sorts of things in the last 10 years anyway, so they’ve already been complying with that IDA requirement for shielded lighting and the correct lumens.” The ordinance passed by the city council does require the city itself to take more action to reach IDA compliance, with new rules for municipal buildings. The ordinance prevents any municipal building from adding new outdoor lighting at night, unless the city manager deems it necessary for public safety, in addition to seeking curfews, motion detectors, and other efforts to limit unnecessary light pollution for existing municipal lighting. A major effect of the new ordinance is to put a timeline on bringing the city into IDA compliance within 10 years, the ordinance states in reference to government properties. Astronomy fanatics in the Verde Valley have long pushed for more municipalities in the area to work to darken their skies and get IDA certification. They hope that when all have joined Camp Verde, Sedona and VOC, the valley could be designated as an internationally recognized dark-skies area. “This is very important for tourism, and astronomy clubs,” Community Development Manager Berrin Nejad said. “I think Cottonwood deserves that, and that’s why with our neighbors’ movements, it was time for us to take the next step.” Originally published by journalaz.com

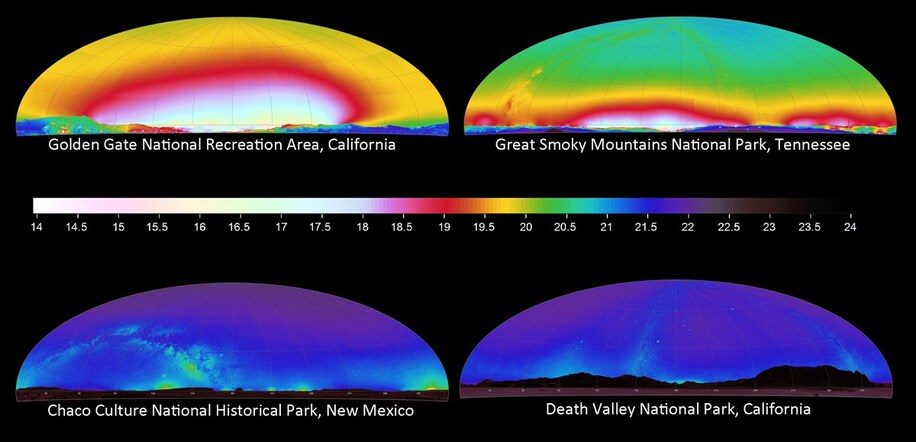

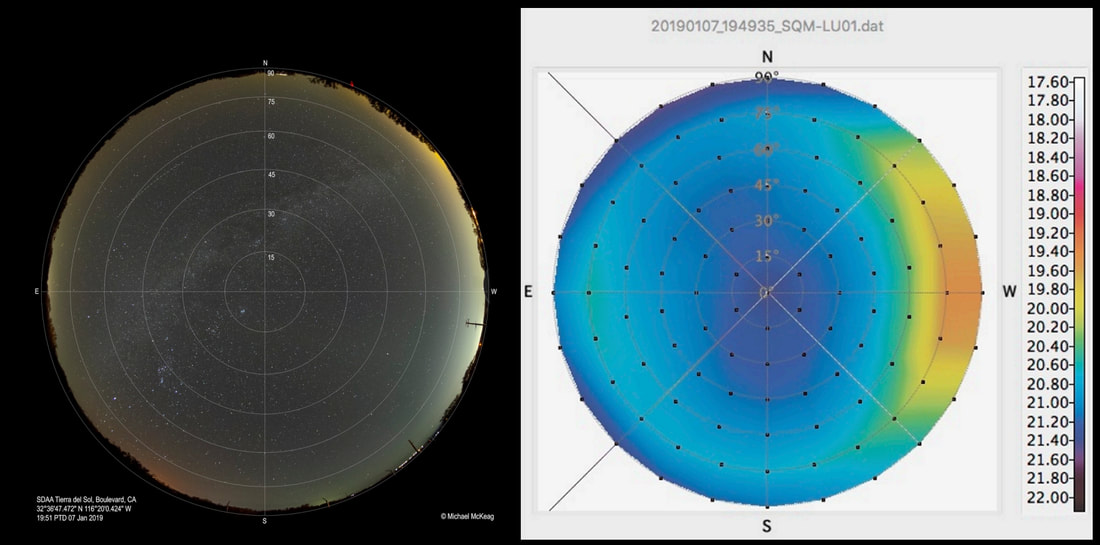

In Praise of Darkness: Henry Beston on How the Beauty of Night Nourishes the Human Spirit BY MARIA POPOVA “Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty,” wrote the Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanizaki in his glorious 1933 love letter to darkness, enveloped in a lament about the perils of excessive illumination. It seems like, having never quite grown out of our perennial childhood fear of the dark, at some point in the twentieth century we took Carl Jung’s poetic assertion that “the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being” a little too literally and set out to illuminate darkness into nonexistence. But darkness — like silence, like solitude — belongs to that class of blessings increasingly endangered in modern life yet vitally necessary to the human spirit. No one has captured the enchantment of darkness and its eternally reigning queen, the night, more beautifully than writer and naturalist Henry Beston (June 1, 1888–April 15, 1968), who in his 1928 classic The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod does for night what Rebecca Solnit has done for walking and Robin Wall Kimmerer for moss. In the eight chapter, titled “Night on the Great Beach,” Beston writes: Our fantastic civilization has fallen out of touch with many aspects of nature, and with none more completely than night. Primitive folk, gathered at a cave mouth round a fire, do not fear night; they fear, rather, the energies and creatures to whom night gives power; we of the age of the machines, having delivered ourselves of nocturnal enemies, now have a dislike of night itself. With lights and ver more lights, we drive the holiness and beauty of night back to the forests and the sea; the little villages, the crossroads even, will have none of it. Are modern folk, perhaps, afraid of the night? Do they fear that vast serenity, the mystery of infinite space, the austerity of the stars? Having made themselves at home in a civilization obsessed with power, which explains its whole world in terms of energy, do they fear at night for their dull acquiescence and the pattern of their beliefs? Be the answer what it will, to-day’s civilization is full of people who have not the slightest notion of the character or the poetry of night, who have never even seen night. Yet to live thus, to know only artificial night, is as absurd and evil as to know only artificial day. But Beston’s prescient admonition fell on deaf ears — nearly a century later, our reliance on this circadian artificiality has reprogrammed our internal clocks to a dangerous degree. In fact, our relationship with darkness and the poetry of night has always been complicated, shrouded in various superstitions and cultural taboos. So absurd were some of them that when trailblazing astronomer Maria Mitchell began teaching the first university class of women astronomers, female students were not allowed to go outside after dark. And yet here we are a century and a half later, having replaced the sociocultural obstructions with technological ones — light pollution is blocking our view of the night, cutting off our eternal supply of Ptolemy’s cosmic ambrosia. Beston describes one particularly poetic night, made pitch-black by the embrace of a thick fog — a night unseen by most of us, and perhaps one already unseeable a century of rabid illumination later. And yet his writing alone transports us to this glorious dominion of darkness, making its magic maybe, just maybe, a little more attainable for us nightless moderns: Night is very beautiful on this great beach. It is the true other half of the day’s tremendous wheel; no lights without meaning stab or trouble it; it is beauty, it is fulfillment, it is rest. Thin clouds float in these heavens, islands of obscurity in a splendor of space and stars: the Milky Way bridges earth and ocean… It was dark, pitch dark to my eye, yet complete darkness, I imagine, is exceedingly rare, perhaps unknown in outer nature. The nearest natural approximation to it is probably the gloom of forest country buried in the night and cloud. Dark as the night was here, there was still light on the surface of the planet. Standing on the shelving beach, with the surf breaking at my feet, I could see the endless wild uprush, slide, and withdrawal of the sea’s white rim of foam. But Beston’s meditation on darkness and the night is ultimately an invitation rather than a lament: Learn to reverence night and to put away the vulgar fear of it, for, with the banishment of night from the experience of man, there vanishes as well a religious emotion, a poetic mood, which gives depth to the adventure of humanity. By day, space is one with the earth and with man — it is his sun that is shining, his clouds that are floating past; at night, space is his no more. When the great earth, abandoning day, rolls up the deeps of the heavens and the universe, a new door opens for the human spirit, and there are few so clownish that some awareness of the mystery of being does not touch them as they gaze. For a moment of night we have a glimpse of ourselves and of our world islanded in its stream of stars — pilgrims of mortality, voyaging between horizons across eternal seas of space and time. Fugitive though the instant be, the spirit of man is, during it, ennobled by a genuine moment of emotional dignity, and poetry makes its own both the human spirit and experience. The Outermost House is an immensely enchanting read in its entirety, uncovering and recovering the civilization-shrouded shimmer of such beautiful phenomena as birds, the beach, midwinter, and high tide. Complement it with Georgia O’Keeffe’s equally bewitching celebration of the Southwestern sky. Originally published on Brain Pickings The IDA adopted new Dark Sky Park designation requirements in June 2018 that not only specified a new minimum Sky Quality Meter (SQM) reading at the zenith of 21.2 magnitudes per square arcsecond or better, but additionally required any artificial light domes on the horizon to be “dim, restricted in extent, and close to the horizon.” So far, the only agency and process that has been able to show or measure this reliably has been the National Park Service using a complex and expensive data reduction scheme and high resolution camera system to map the whole night sky at current and proposed NPS dark sky sites. The complexity and expense of this system has been a significant constraint to making valid and reliable evaluations at non-NPS sites. Bob Yoesle (recipient of an IDA 2015 Dark Sky Defender Award) and Micheal McKeag (IDA Oregon Delegate), amateur astronomers, dark sky advocates, and members of the Rose City Astronomers in Portland Oregon, have been working on devising a methodology for standardizing the process of assessment with simpler, more readily available and less expensive equipment and methods. This is needed for ongoing assessment of the scenic impacts of light pollution in the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, as well as proposed dark sky sites and communities both in the Pacific Northwest and around the world. Mike has used a high-quality wide-angle “fisheye” lens to do whole sky DSLR imagery, combined with Uniheadron SQM readings made on an alt-azimuth computer-controlled telescope mount. Unfortunately, due to the wide field of view of the SQM device, this has proved unsatisfactory for light dome measurements along the horizon:

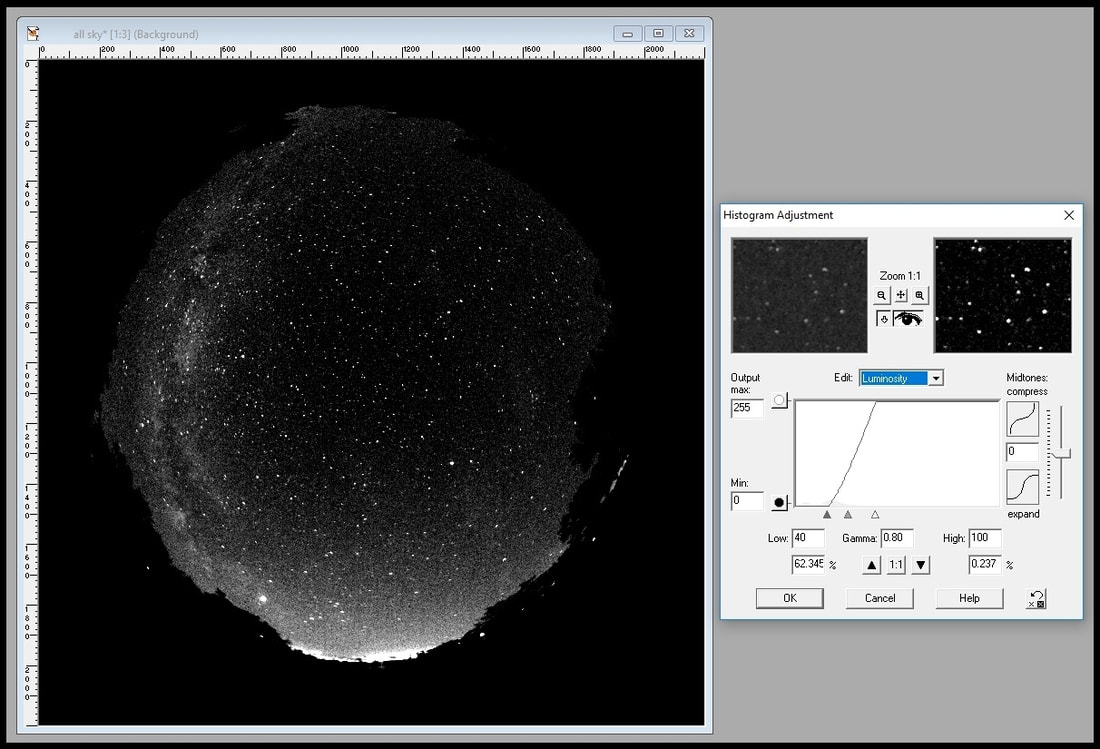

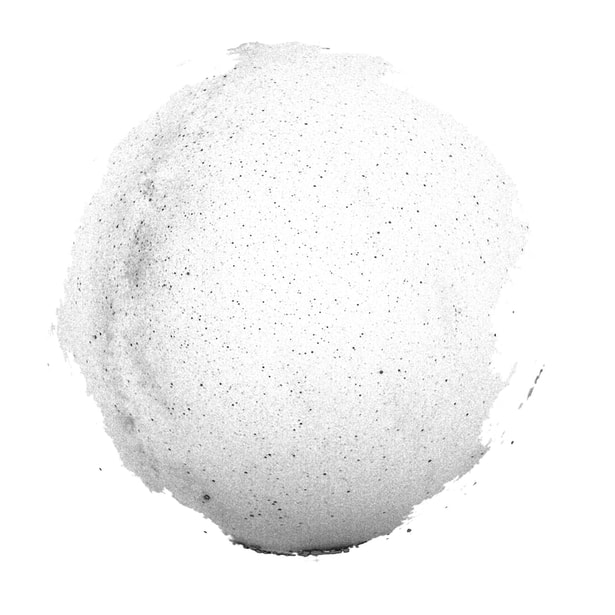

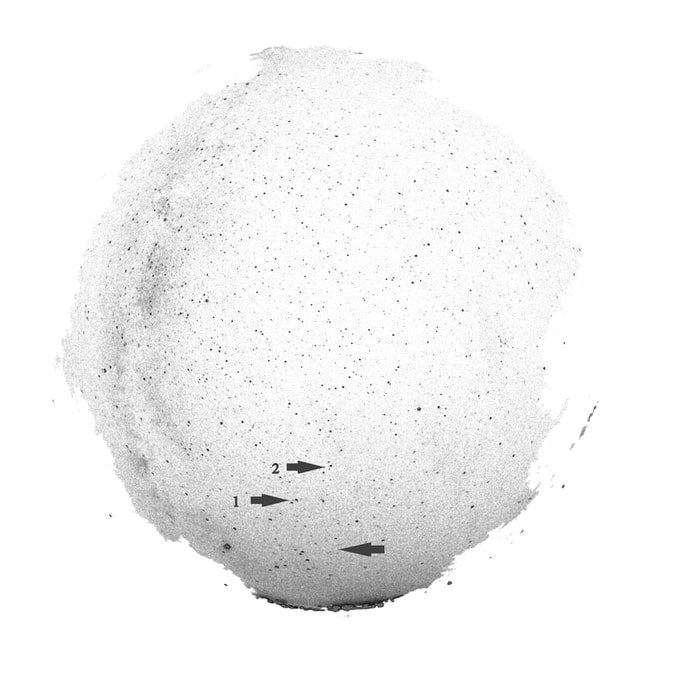

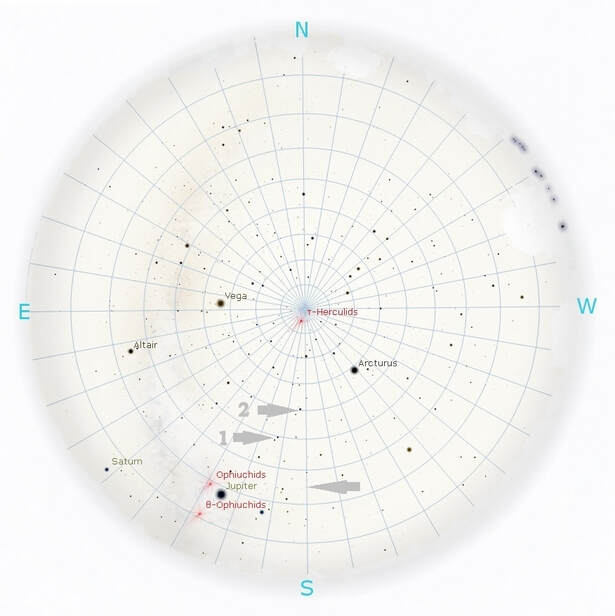

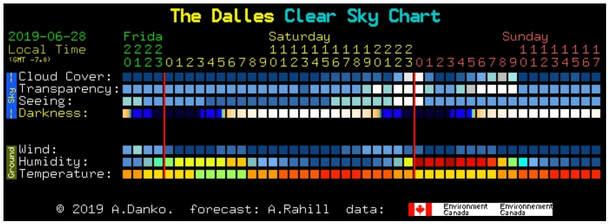

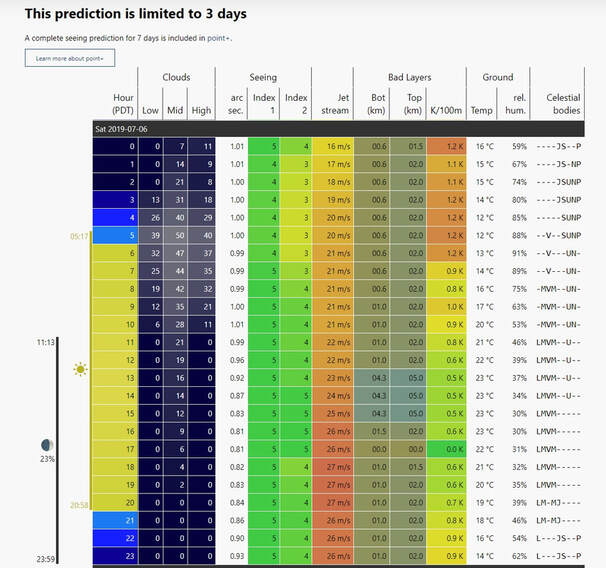

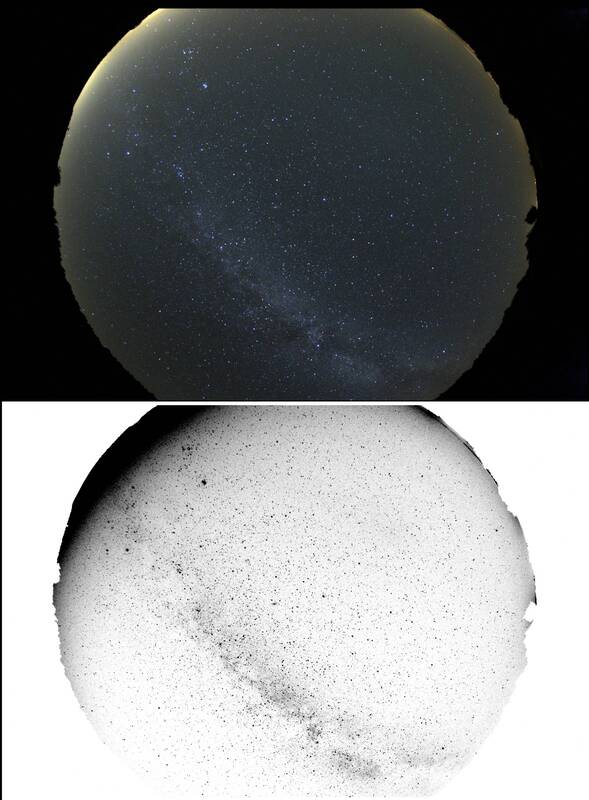

Until a narrower angle SQM with a field of sensitivity which will allow higher resolution and substantial enough improvements to be used in mapping horizon light domes comes along, Bob has devised and proposed a photographic methodology that directly compares light dome brightness to the brightness of the Milky Way, whose visibility is a key feature and requirement of any dark sky location. All that is required for this methodology is a fisheye lens all-sky imaging system of good quality. But you don't need a dedicated camera system - Bob used a sturdy photo tripod, DSLR camera, and one of the least expensive fisheye lenses available. The only other requirements are a digital photo processing program such as Photshop, Paint Shop Pro, etc. that allows histogram adjustment, and a planetarium program which is able to show azimuth and altitude angles of indicator stars above the horizon. This procedure is simple and affordable enough for amateurs astronomers and photo enthusiasts of all ages and skill levels to perform with minimal experience. The first thing to do is to take a picture that sufficiently exposes the night sky enough to capture the Milky Way: This image is then converted to a black and white “greyscale” image: The image histogram is then adjusted to stretch midtones and suppress/eliminate the shadows and highlight regions of the image. This makes any light pollution much more evident and also enhances the brightness of the Milky Way to give a good set of comparison levels of brightness: Using modified histogram settings to make adjustments to the image can highlight both the Milky Way and the extent of light pollution domes. This qualitative process requires different settings for varying exposures, yet appears to be a useful tool in extracting the true extent of artificial sky glow compared to the original image. Depending on the dynamics of the image, a negative image can sometimes provide better contrast to make the extent of faint levels of light more evident (our eyes often work better with black stars on a white background verus the opposite): One of the limitations of using a wide angle fisheye lens for all sky imaging is the distortion and foreshortening of features which occurs near the horizon: Using a planetarium program such as Stellarium (a free download), one can easily judge the extent of artificial brightness along the horizon and how far such artificial brightness reaches into the sky: A qualitative exam of light dome extent. The unlabeled arrow points to β1 Sco at the top of the three pincer stars of Scorpius, arrow 1 lies between δ and ε Oph, and arrow 2 lies between α and ε Ser. These areas represent areas similar in brightness to the Milky Way going from the brightest to the dimmest discernible areas in the image. In this case we can see the altitude above the horizon for these parts of the light dome ~ 25, 40, and 50 degrees respectively: Around the new moon, a series of these images can be taken over a period of hours, days, or months to get a more valid sample of the site’s overall night sky quality. When combined with concurrent zenith SQM readings, the reliability of such a methodology can be readily established. Bob suggests use of a nearby Clear Sky Chart location or similar application prior to an imaging run to establish the general conditions locally under which the data and images are obtained: The IDA has responded favorably to this methodology for future dark sky site evaluations. Dark Sky Defenders welcomes contributions and refinements others may come up with to enhance or improve upon this methodology. Please use the Contact Page to send us your input and suggestions. Written by Ryann Richards on June 18, 2019  Photo by Mark Basarab ST. GEORGE — Residents in Ivins are coming together to find creative solutions to light pollution. The Ivins Night Sky Initiative was founded in January with hopes to “improve, preserve, and protect the night sky over Ivins,” according to its website. Director Mike Scott said the organization and Ivins residents are seeking to modify an outdoor lighting ordinance due to its outdated nature. The ordinance is about 12 years old. They are looking to reduce the color temperature of outdoor lighting to soften the “harsh white light” and reduce blue light emissions, he said. Reducing blue light will not only decrease sky glow and light pollution, but it will also benefit the safety of the community as it will reduce glare. Scott said the change will also protect residents’ health as recent studies have found that blue light contributes to a number of adverse health effects, including greater risk of heart disease, some cancers and permanent eye damage. While the city of Ivins waits for the proposed changes to make their way through local government, residents are making their own, temporary solutions to current light pollution concerns. The goal of the do-it-yourself solutions is to aim the light in a more effective manner while limiting the effect that “stray light” has on the night sky, Scott said. This can be accomplished by focusing the light into a downward beam and limiting blue light. “We’re not trying to reduce outdoor lighting, exactly,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is just make sure that it aims the light where we really want it to go.” One resident used red Solo cups to aim the beam of light more downward and block any upward light from shooting into the sky. Eagle Rock, a subdivision with about 90 homes, changed the lights outside of garages to focus the light downward. Scott said most outdoor lighting in the future is going to consist of LED bulbs, which are efficient and economically friendly, but LEDs include quite a bit of blue light. Ivins has been getting the best of both worlds by using LED lights with an amber filter. “So you get rid of the harmful potential health risk and safety problems,” he said. Ivins was cognizant of the night sky when drafting the ordinance a dozen years ago, Scott said, but the technology has changed and the city is growing almost as rapidly as St. George. He said Ivins is projected to double in size over the next 20 years. With this in mind, the Ivins Dark Sky Initiative is looking to impact the present in order to start on the best foot for the future. “We are going to grow,” Scott said. “We are going to need a lot more outdoor lighting, so let’s just make sure it’s the best kind of lighting we can possibly have.” The organization now has about 25 volunteers who work to educate people about light pollution and the harmful effects of blue light. It is working with the International Dark Sky Association and is hoping to have Ivins named as a “Dark Sky Community” within the next year. In order for Ivins to be considered for the designation the city must meet a set of requirements, including a lighting policy that covers shielded lamp posts and blue light restrictions and the opportunity for education and community outreach. Ivins City Council will consider the lighting design and construction plans for outdoor lighting at its meeting on June 20 at 5:30 p.m. at Ivins City Hall. St. George News The In-Depth April National Geographic Story on how light pollution is generally getting worse can be found HERE. With the proposed release of thousands of near Earth orbit SpaceX "Starlink" satellites, astronomers and dark sky advocates fear the worst, but are hoping for the best. Statement from the International Dark-Sky Association Tucson, AZ – On May 23, 2019, the spacecraft company, SpaceX launched a group of sixty satellites into low Earth orbit (LEO). Due to their reflective solar panels and other metal surfaces, the satellites are visible to the naked eye at night. In the days since they were launched, sightings have been reported all around the world. The visibility of the satellites, combined with a rapid increase in the number of satellites in LEO has caused concern in the astronomy and stargazing communities. Questions about the impact of this newly deployed technology are rippling through the natural nighttime conservation network. To date, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission has already approved the operation of more than 7,000 SpaceX satellites in low Earth orbit. At least three other companies have expressed interest in launching large groups of similar new satellites, which are intended to provide reliable broadband internet service to people all over the world. These plans could easily lead to tens of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit. The rapid increase in the number of satellite groups poses an emerging threat to the natural nighttime environment and our heritage of dark skies, which the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) has worked to protect since 1988. We do not yet understand the impact of thousands of these visible satellites scattered across the night sky on nocturnal wildlife, human heritage, or our collective ability to study the cosmos. Some early reports have caused concern. James Lowenthal, a professor of astronomy at Smith College, was training undergraduate students for a summer astronomy outreach internship in New Hampshire when the SpaceX satellite grouping crossed their path in the night sky. “We were gathered around the telescope when one of them shouted, ‘WHAT is THAT?’” he tells IDA. Lowenthal calls the satellites a “shocking and devastating sight.” The number of low Earth orbit satellites planned to launch in the next half-decade has the potential to fundamentally shift the nature of our experience of the night sky. IDA is concerned about the impacts of further development and regulatory launch approval of these satellites. We therefore urge all parties to take precautionary efforts to protect the unaltered nighttime environment before deployment of new, large-scale satellite groups. SpaceX Satellites Pose New Headache For Astronomers Issam Ahmed, Physics.org It looked like a scene from a sci-fi blockbuster: an astronomer in the Netherlands captured footage of a train of brightly-lit SpaceX satellites ascending through the night sky this weekend, stunning space enthusiasts across the globe. But the sight has also provoked an outcry among astronomers who say the constellation, which so far consists of 60 broadband-beaming satellites but could one day grow to as many as 12,000, may threaten our view of the cosmos and deal a blow to scientific discovery. The launch was tracked around the world and it soon became clear that the satellites were visible to the naked eye: a new headache for researchers who already have to find workarounds to deal with objects cluttering their images of deep space. "People were making extrapolations that if many of the satellites in these new mega-constellations had that kind of steady brightness, then in 20 years or less, for a good part the night anywhere in the world, the human eye would see more satellites than stars," Bill Keel, an astronomer at the University of Alabama, told AFP. The satellites' brightness has since diminished as their orientation has stabilized and they have continued their ascent to their final orbit at an altitude of 550 kilometers (340 miles). But that has not entirely allayed the concerns of scientists, who are worried about what happens next. Elon Musk's SpaceX is just one of a several companies looking to enter the fledgling space internet sector. To put that into context, there are currently 2,100 active satellites orbiting our planet, according to the Satellite Industry Association. If another 12,000 are added by SpaceX alone, "it will be hundreds above the horizon at any given time," Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told AFP, adding that the problem would be exacerbated at certain times of the year and certain points in the night. "So, it'll certainly be dramatic in the night sky if you're far away from the city and you have a nice, dark area; and it'll definitely cause problems for some kinds of professional astronomical observation." Musk's puzzling response The mercurial Musk responded to the debate on Twitter with contradictory messages, pledging to look into ways to reduce the satellites' reflectivity but also saying they would have "0% impact on advancements in astronomy" and that telescopes should be moved into space anyway. He also argued the work of giving "billions of economically disadvantaged people" high-speed internet access through his network "is the greater good." Keel said he was happy that Musk had offered to look at ways to reduce the reflectivity of future satellites, but questioned why the issue had not been addressed before. If optical astronomers are concerned, then their radio astronomy colleagues, who rely on the electromagnetic waves emitted by celestial objects to examine phenomena such as the first image of the black hole discovered last month, are "in near despair," he added. Satellite operators are notorious for not doing enough to shield their "side emissions," which can interfere with the observation bands that radio astronomers are looking out for. "There's every reason to join our radio astronomy colleagues in calling for a 'before' response," said Keel. "It's not just safeguarding our professional interests but, as far as possible, protecting the night sky for humanity." Lights In The Sky From Elon Musk's New Satellite Network Have Stargazers Worried Michael J. I. Brown, The Conversation UFOs over Cairns. Lights over Leiden. Glints above Seattle. What's going on? The launch of 60 Starlink satellites by Elon Musk's SpaceX has grabbed the attention of people around the globe. The satellites are part of a fleet that is intended to provide fast internet across the world. Improved internet services sound great, and Musk is reported to be planning for up to 12,000 satellites in low Earth orbit. But this fleet of satellites could forever change our view of the heavens. Starlink's ambitious mission Starlink is an ambitious plan to use satellites in low Earth orbit (about 500km up) to provide global internet services. This is different from the approach previously used for most communication satellites, in which larger individual satellites were placed in high geosynchronous orbits—that stay in an apparently fixed position above the Equator (about 36,000km up). Communications with satellites in geosynchronous orbits often require satellite dishes, which you can see on the sides of residential apartment buildings. Communication with satellites in low Earth orbit, which are much closer, won't require such bulky equipment. But the catch with satellites in low Earth orbit, which move quickly around the world, is they can only look down on a small fraction of the globe, so to get global coverage you need many satellites. The Iridium satellite network used this approach in the 1990s, using dozens of satellites to provide global phone and data services. Starlink is far more ambitious, with 1,600 satellites in the first phase, increasing to 12,000 satellites during the mid-2020s. For comparison, there are roughly 18,000 objects in Earth orbit that are tracked, including about 2,000 functioning satellites. Starlink satellites travel silently across the skies of Leiden. Lights in the sky It's not unusual to see satellites travelling across the twilight sky. Indeed, there's a certain thrill to seeing the International Space Station pass overhead, and to know there are people living on board that distant light. But Starlink is something else. The first 60 satellites, launched by SpaceX last week, were seen travelling in procession across the night sky. Some people knew what they were seeing, but the silent procession of light also generated UFO reports. If you're lucky, you may see them pass across your skies tonight. If the full constellation of satellites is launched, hundreds of Starlink satellites will be above the horizon at any given time. If they are visible to the unaided eye, as suggested by initial reports, they could outnumber the brightest natural stars visible to the unaided eye. Astronomers' fears were not put to rest by Musk's tweets: Satellites are very definitely visible at night, particularly in the hours before dawn and after sunset, as they are high enough to be illuminated by the Sun. The Space Station's artificial lighting is effectively irrelevant to its visibility. In areas near the poles, including Canada and northern Europe, satellites in low Earth orbit can be illuminated throughout the night during the summer months. Hundreds of satellites being visible to the unaided eye would be a disaster. They would completely ruin our view of the night sky. They would also contaminate astronomical images, leaving long trails across otherwise unblemished images. The US$466 million Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, based in Chile, is an 8-metre aperture telescope with a 3,200-megapixel camera. It's designed to rapidly survey the sky during the 2020s. Will we lose the night sky to city lights and satellites? Credit: Jeff Sullivan, CC BY-NC-NDWith the full constellation of Starlink satellites, many images taken with this telescope will contain a Starlink satellite. Longer exposures could contain dozens of satellite streaks. Dark skies or darkened hopes? Is there any cause for optimism? Yes and no. Musk has produced some amazing feats of technology, such as the SpaceX Falcon and Tesla cars, but he's also disappointed some on other projects, such as the Hyperloop tunnel transport plan. While Starlink certainly blew up on Twitter, for now at least, Musk is 11,940 satellites short of his 12,000. Also, initial reports may have overestimated the brightness of the Starlink satellites, with the multiple satellites closely clustered together being confused with one satellite. While some reports have indicate binoculars are needed to see the individual satellites, they also report that Starlink satellites flare, momentarily becoming brighter than any natural star. If the individual satellites usually are too faint to be seen with the unaided eye, that would at least preserve the natural wonder of the sky. But professional astronomers like myself may need to prepare for streaky skies ahead. I can't say I'm looking forward to that. Cloudy Nights contributor t image created the graphic animation below to simulate the visibility of the SpaceX satellites:

Thanks to the code written by Astronomy Live's youtube channel owner, I generated TLE's for 66 satellites in 24 orbital planes at 550km to simulate the planned first shell of Starlink satellites. I created an animation from an arbitrary location, I chose Long Island, New York since it is near a large population. This is if there were 1,584 Starlink satellites up and place right now, each frame is a 10 minute change in time, as can be read. Note the promise that you won't be able to see them deep into a summer night is not necessarily factual. The satellite icons shown indicate they will be reflecting Sunlight. However, their brightness may be in the range of mag. 4- mag 10 or dimmer, depending on time/location/orientation. Flares are also not animated as the operational orientation is not yet known thus not making them predictable. Expect flares to be up to mag. 1 or brighter depending on reports so far... Join the International Dark-Sky Association for a week of celebration, learning, and action!

2019 International Dark Sky Week is Sunday, March 31 – Sunday, April 7! Created in 2003 by high-school student Jennifer Barlow, International Dark Sky Week has grown to become a worldwide event and a key component of Global Astronomy Month. Each year it is held in April around Astronomy Day. This year celebrations begin on Sunday, March 31, and run through Sunday April 7, 2019 (click here for resources to use during the week). In explaining why she started the week, Barlow said, “I want people to be able to see the wonder of the night sky without the effects of light pollution. The universe is our view into our past and our vision into the future. … I want to help preserve its wonder.” International Dark Sky Week draws attention to the problems associated with light pollution and promotes simple solutions available to mitigate it. Also read “5 Ways to Celebrate Dark Sky Week“! Light Pollution Matters The nighttime environment is a crucial natural resource for all life on Earth, but the glow of uncontrolled outdoor lighting has hidden the stars, radically changing the nighttime environment. Before the advent of electric light in the 20th century, our ancestors experienced a night sky brimming with stars that inspired science, religion, philosophy, art and literature including some of Shakespeare’s most famous sonnets. The common heritage of a natural night sky is rapidly becoming unknown to the newest generations. In fact, millions of children across the globe will never see the Milky Way from their own homes. We are only just beginning to understand the negative repercussions of losing this natural resource. A growing body of research suggests that the loss of the natural nighttime environment is causing serious harm to human health and the environment. For nocturnal animals in particular, the introduction of artificial light at night could very well be the most devastating change humans have made to their environment. Light pollution also has deleterious effects on other organisms such as migrating birds, sea turtle hatchlings, and insects. Humans are not immune to the negative effects of light in their nighttime spaces. Excessive exposure to artificial light at night, particularly blue light, has been linked to increased risks for obesity, depression, sleep disorders, diabetes and breast cancer. Good Lighting Doesn’t Compromise Safety & Security There is no clear scientific evidence that increased outdoor lighting deters crime. It may make us feel safer but it does not make us safer. The truth is bad outdoor lighting can decrease safety by making victims and property easier to see. Glare from overly bright, unshielded lighting creates shadows in which criminals can hide. It also shines directly into our eyes, constricting our pupils. This diminishes the ability of our eyes to adapt to low-light conditions and leads to poorer nighttime vision, dangerous to motorists and pedestrians alike. Another serious side effect of light pollution is wasted energy. Wasted energy costs money, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, and compromises energy security. What YOU Can Do The good news is that light pollution is reversible and its solutions are immediate, simple and cost-effective. Here are a few simple things you can do to confront the problem and take back the night: • Check around home. Shield outdoor lighting, or at least angle it downward, to minimize “light trespass” beyond your property lines. Use light only when and where needed. Motion detectors and timers can help. Use only the amount of light required for the task at hand. • Attend or throw a star party. Many astronomy clubs and International Dark Sky Places are celebrating the week by holding public events under the stars. See our Events Calendar to find an event in your area (we update our calendar regularly, so be sure to keep checking back). If you have a dark sky related event, please let us know, so we can post it! • Download, Watch, and Share “Losing the Dark,” a public service announcement about light pollution. It can be downloaded for free and is available in 13 languages. • Talk to neighbors and your community. Explain that poorly shielded fixtures waste energy, produce glare and reduce visibility. Need inspiration? Check out our Get Involved page and our public outreach resources. • Become a Citizen Scientist with GLOBE at Night or the Dark Sky Rangers and document light pollution in your neighborhood and share the results. Doing so, contributes to a global database of light pollution measurements. • Explore Online. Join us on Facebook and Twitter (hashtag #IDSW2019). Newport State Park is the first state park in Wisconsin designated by IDA as an International Dark Sky Park, one of just 48 parks in the world to earn the distinction. Located at the northern tip of Door County on the western shore of Lake Michigan, Newport has a dark sky that offers excellent nighttime viewing with an unobstructed view of the eastern horizon. As a designated wilderness park, the park has minimal development beyond the park office and a picnic area with a park shelter. “After more than 15 years, IDA International Dark Sky Places is still a program of firsts, and today is no exception,” said IDA Executive Director J. Scott Feierabend. “Newport’s entry into the IDA family of International Dark Sky Parks is a welcomed development for Wisconsin and the protection of dark skies in the upper Midwest United States.” With the designation, Newport joins the ranks of only 13 other state parks in the United States to have received IDA accreditation. “The prestigious Dark Sky Park designation opens the park to local, regional, national and international astronomical clubs and societies, increasing tourism, especially ecotourism. Obtaining this honor will accord national and international recognition to Newport State Park and the Wisconsin State Park system,” said Ben Bergey, Wisconsin State Park System director. The idea for applying for the designation began four years ago when Ray Stonecipher, a local Door County amateur astronomer and member of the Door Peninsula Astronomical Society, approached Park Superintendent Michelle Hefty about seeking the designation. “In a modern world that is accompanied by ever increasing levels of nighttime illumination, a truly dark sky at night is rare and unique,” explained Hefty. Sensing the value of dark night skies at Newport, Hefty agreed to formally launch the certification effort. Newport’s supporting partners for the Dark Sky Park project include the Door Peninsula Astronomical Society, the Newport Wilderness Society, the parks friends group, and a committee of dedicated volunteers. Park staff carried out the work to complete the lengthy application and will continue to ensure the park meets IDA guidelines. “From lighting projects to community education and outreach, our commitment to protect our dark sky is a priority we take seriously,” said Beth Bartoli, a Newport State Park naturalist who helps conduct astronomy programs at the park. “We never tire of seeing that ‘aha moment’ on the upturned faces of our visitors as they gaze toward the heavens.” The park hosted a dedication ceremony at the time an official International Dark Sky Park sign was placed in the park. The ceremony featured talks by members of the Door Peninsula Astronomical Society and Newport Wilderness Society as well as local officials. For more information about Newport State Park, visit the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources website. The night sky has become a tourist destination, and stargazers can enjoy it near and far, from the dry heights of Chile's Atacama Desert to monthly meetings at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Terri Colby Chicago Tribune December 3, 2018 The night sky has become a tourist destination. But wait a minute. Can’t we see the night sky simply by stepping outside after dark and looking up? Well, yes. But for most of us, that means seeing the glow from artificial lights reflecting off clouds, water vapor and dust particles in the air. It’s called sky glow; the night sky is so bright, it’s hard to see the stars. For most of the time people have lived on this planet, the night sky was inky dark and filled with visible celestial objects. It’s inspired poets and dreamers, artists and scientists, linking humankind with its past and perhaps its future, as people looked to the sky to ponder life’s mysteries. It’s only been in the last 100 years or so that light and air pollution have diminished those views. And it’s only been in recent years that people have started traveling in search of what has been lost, whether it’s seeking out spots close to home in the Midwest or venturing farther afield in the Southern Hemisphere. “We’re seeing dark-sky tourism as a reaction against our increasingly busy, tech-filled lives,” said Daniel Levine, a travel trends expert and director of the Avant-Guide Institute, a global trends consultancy. “It’s a chance to decompress, be somewhere quiet and be awed by the biggest question in life: Why are we here?” Hoping for a dark-sky experience, myself, earlier this year, I headed to a mountain plateau west of the Andes in Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth and a mecca for astronomers and stargazers. I settled in at the small town of San Pedro de Atacama with plans to do some stargazing and to visit the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. Better known as ALMA, it’s billed as the “most complex astronomical observatory ever built on Earth” by the U.S.-based National Radio Astronomy Observatory. In cooperation with the Chilean government, an international partnership from North America, Europe and East Asia built and operates the facility. Scientists from around the world share time on the telescopes for research. The town is a tourist center with muted lighting and dirt streets lined with restaurants, souvenir shops and tour operators offering desert adventures. It seemed there was a stargazing operator on every block. I worked with Astronomic Tour Licanantay Observatory, a company that mixes astronomy with culture to explore the night sky and how it was interpreted by the ancient Atacameno people. (Another good option is San Pedro de Atacama Celestial Explorations, or SPACE. Except for the days around the full moon, both companies offer nightly tours leaving from San Pedro.) A late-night, half-hour bus ride took me out of town into the desert. After climbing out of the bus, I stopped in my tracks. It was so dark I couldn’t see the ground. But no one needed to point out the Milky Way: There it was up above, a vast streak composed of billions upon billions of stars packed so close together, it seemed as though one blended into another. These “envoys of beauty” (Ralph Waldo Emerson) and “jewels of the night” (Henry David Thoreau) that made Vincent van Gogh paint masterpieces were on display for me in a place where the ancient Atacamenos were long-ago astronomers. About a dozen people on our tour spent the next hour sitting on wooden benches lining a raised platform while a guide pointed out the stars, constellations and planets. He talked about the people who lived here long ago, when there were so many stars twinkling in the skies that people named the dark spaces in between them, similar to the way we name constellations. We had a telescope at our disposal for magnified viewing, but I preferred just looking up and listening to him talk. Before it was over, each of us posed for a photo with the Milky Way as a backdrop, providing a nice souvenir. The next morning, I got a tour that was decidedly more scientific at ALMA’s Operations Support Facility, an engineering marvel open to the public Saturday and Sunday mornings. Admission is free, but it’s best to make a reservation well in advance at almaobservatory.org/en. Click on “Outreach” and “Visits.” Perched 6,000 feet above the operations facility, the radio telescopes aren’t within view of the public, but people can see the data pouring into computers monitored by scientists. The facility has an extensive education program that can keep visitors entertained for hours. Because most of us don’t have access to clear skies like those in the Atacama, destinations offering dark-sky experiences have become tourist attractions. It’s part of a larger trend of so-called astro tourism, according to Levine, the travel trends expert. “We are living in a new age of space awareness,” he said. “People are looking to the skies as never before.” Witness the crowds who traveled to see the solar eclipse in 2017, and others taking trips to experience the Northern Lights. Even before astro tourism took off, the International Dark-Sky Association had raised the alarm that the visible night sky is a vanishing natural wonder. Formed 30 years ago, the association has designated more than 100 locales around the world as dark-sky places, ranging from light pollution-minded suburbs like Homer Glen and the small Indiana town of Beverly Shores, where shields on street lighting keep the illumination focused downward, to dark sky parks in the Southwest U.S. and much larger reserves or sanctuaries in places such as Namibia and New Zealand. Utah has the world’s highest concentration of IDSA-certified parks, some of which offer regular stargazing events. In northern Michigan, the Headlands International Dark Sky Park in Mackinaw City gained IDSA certification in 2011. The park includes more than 500 acres of woodlands along 2 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline, as well as an events center and a guest house that can sleep 22 people. With miles of hiking trails and kid-friendly outdoor sky exhibits, it’s a great place to visit during the day. But at night, it’s for relaxing and pondering the cosmos. The first night I was at Headlands, clouds obscured the scene, and the bugs at sunset were intense. On our second night, the sky came alive, slowly. The first stars to show up were actually planets, Venus and Jupiter, before sunset. A midsummer night with no moon was perfect for stargazing, but the full sunset was a long time coming. While daylight lingered, a park astronomer guided visitors to a telescope set up on a patio along the lakeshore. As the skies darkened, most folks preferred to just look up and watch as more and more stars surfaced and the pink-tinted, blue-gray sky slowly turned black. The star show at Headlands wasn’t a match for the ideally dry skies of Chile, but for most city residents, it’s an extravaganza well worth the trip. Not many of the official dark-sky places are close to large metropolitan areas, for obvious reasons. That’s what makes the Beverly Shores community designation special; it’s within reach of millions of people. On the banks of Lake Michigan, across the water from Chicago, Beverly Shores is surrounded by the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Just outside of town, in the parking lot for Kemil Beach, amateur astronomers share their telescopes at monthly stargazing events.

“When I was a kid, you could drive out of the city and into the darkness, but these little islands of darkness are disappearing,” said Larry Silvestri, who helps run the stargazing at Kemil Beach. “But here, 10 million people in this region can come and see the Milky Way.” Terri Colby is a freelance writer. The Consortium for Dark Sky Studies The Human Heritage of Dark Skies For many people, simply remembering the dark skies and starry nights of their youth and wanting that experience for their children and children’s children is the impetus behind their support of dark sky efforts. Until several generations ago, before urbanization and the widely available technological ability to overwhelm a landscape with lighting, the stars at night were part of the universal human experience; now an estimated 80% of the developed world is unable to see the Milky Way. Dark Skies as Resources Natural resource A natural resource is anything that people can use which comes from nature, such as air, water, wood, oil, wind energy, iron, and coal. Dark skies are a guilt-free natural resource: no extraction cost or risk of environmental damage by virtue of its use. And, with energy savings there is even payback for replenishing and preserving the dark skies, an unusual and distinctly virtuous cycle. Cultural resource Cultural resources are, in the broadest sense, resources significant to human cultures - the ideas, customs, and social behavior of a society. Some are part of the universal human experience, like dark skies, some specific to a group of people at a particular time in history with various interpretations of the night skies. Ethno-astronomy is the study of some of these varieties of interpretation. The human experience of a dark night is expressed in many ways, art, literature, philosophy, film, and others. Economic resource Economic resources are the factors used in providing services (like astro-tourism or dark-sky experiences) or producing goods. A dark sky is widely used as a way to develop sustainable destination economies for scenic gateway communities in the American West. Dark Sky Consortium Studies Program Takes Shape Written by Colter Dye Bridging the borders of three great North American ecosystems: the Great Basin, the Colorado Plateau, and the Rocky Mountains, Salt Lake City is a popular destination for wildlife enthusiasts, outdoor adventurers, and those seeking to connect to the natural world. While snow-capped mountain peaks, vast red deserts, and tree-filled canyons are majestic, one of the most awe-inspiring views comes from glimpsing an arm of the Milky Way Galaxy against a deep blue night sky. Maintaining a view of our dark skies has implications beyond the inspirational connection to the universe, it is also vital to the health and safety of humans and wildlife as well as our respective ecosystems, which often overlap. The new Consortium for Dark Sky Studies at the University of Utah hopes to preserve access to dark skies. Formal recognition of the Consortium for Dark Sky Studies (CDSS) was made official by the University of Utah, a strategic location for the CDSS as Salt Lake City is central to what Stephen Goldsmith, co-director of the CDSS and associate professor of city and metropolitan planning calls the “Great Starry Way.” “This portion of the West, basically Montana down to New Mexico, is what I would call the Great Starry Way. These are the darkest places left in the developed world – That’s on the planet, on the Earth!” remarked Goldsmith. Many migratory birds, including thrushes, wrens, orioles, black birds, cuckoos, tanagers, and most species of sparrow, make the majority of their seasonal migrations during the nighttime hours. Species may migrate during the nighttime hours to avoid daytime predators, maximize foraging time during the day, navigate using the moon or constellations, or to prevent their bodies from overheating due to hours of wing flapping. These species now have to navigate new challenges in nighttime migration caused by the constant blaring lights emitted from human settlements. Flocks of birds may mistake these glowing metropoles for the shining light of the moon or they may be unable to see the constellations they use to navigate because they are muted by the glowing artificial lights. Other birds seem to mistake gleaming glass windows for the surface of water reflecting moonlight. The fate of many of these birds ends with disorientation or confusion leading to missed navigational points, exhaustion, or a quick demise as they collide with buildings. Each year, in North America alone, anywhere between 365 million and 1 billion birds die from collisions with buildings. Migrating birds are not the only wildlife affected. Many species of frogs wait for cues from the night sky and the moon to cue their breeding rituals of croaking and calling to find a mate. Nocturnal insects are fatally attracted to artificial lights, preventing them from breeding naturally and making them vulnerable to nighttime predators. On the warmer coasts of the world, baby sea turtles search for the twinkling lights of the moon and stars being reflected on the ocean, but are instead drawn toward the glowing lights of roads and cities, leading them to a certain death by car, dehydration, or predation. Humans are also physiologically ruled by the regular pattern of night and day. Exposure to artificial light at night negatively affects the human circadian rhythm which not only affects sleep cycles but also the production of important hormones which regulate vital biological processes. These changes have been linked to depression, obesity, as well as breast and prostate cancers. While most cities have had ordinances in place for many years to regulate noise pollution, very few have paid any attention to the important consequences of light trespass and pollution. The work of the CDSS will help to fill this gap. CDSS affiliates come from many departments of the University of Utah, as well as community, government, and industry partners. Tracy Aviary is an advisor for the CDSS. Beginning in April of 2016, Tracy Aviary began implementing a strategic campaign to decrease light pollution in Salt Lake County, Utah, by holding a series of ‘migration moonwatch’ events to educate the public about the impact of light pollution on migrating birds. In 2017, the Aviary will expand the program to include strategic data collection on birds that strike buildings as a result of light pollution in Salt Lake’s urban core. Building off of strategies from other successful dark skies projects such as FLAP and “lights out,” the Aviary developed the Salt Lake Avian Collision Survey (SLACS), a citizen science project where volunteers will walk early morning survey routes during the migration season to search for and collect data on birds that had collided with lighted buildings overnight. Information collected by SLACS will help target photon reduction strategies and build public support for a “lights out for migration” initiative in Salt Lake. This kind of period of decreased artificial light benefits human communities as well as birds and other wildlife. It reduces the consumption of fossil fuels that are used to power unnecessary lights, potentially saving billions of dollars and reducing pollutant emissions by many tons. It also allows humans living in urban areas to reconnect with the night sky and enjoy the Milky Way, which some people may not have seen for many years and some children may have never seen in their lives. Many communities are even using these lights out periods to host festivals celebrating the night sky, uniting divided populations, and teaching citizens about the wonders of astronomy. With its placement on the foothills of the Wasatch Mountain Range, University of Utah’s campus is one of the only college campuses in the United States that provides a direct connection to wild, undeveloped land and the opportunity for encounters with the natural world. Our special connection to and awareness of the natural world makes our campus the ideal place to continue research on the values of reducing light pollution and implementing practices to restore dark skies to our campus and Salt Lake City. Colter Dye is an undergraduate student pursuing a degree in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation through the Bachelor of University Studies program at the University of Utah. He is a Sustainability Ambassador for the Sustainability Office at the University of Utah. He is also a Conservation Science Intern at Tracy Aviary and an affiliate of the Consortium for Dark Sky Studies at the University of Utah. UTAH'S DARK SKY PLANNING GUIDE Community Development Office |

Archives

March 2024

|

|

Donations to Dark Sky Defenders do not go to DarkSky International. Please contribute directly to DSI for donations and memberships.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed