|

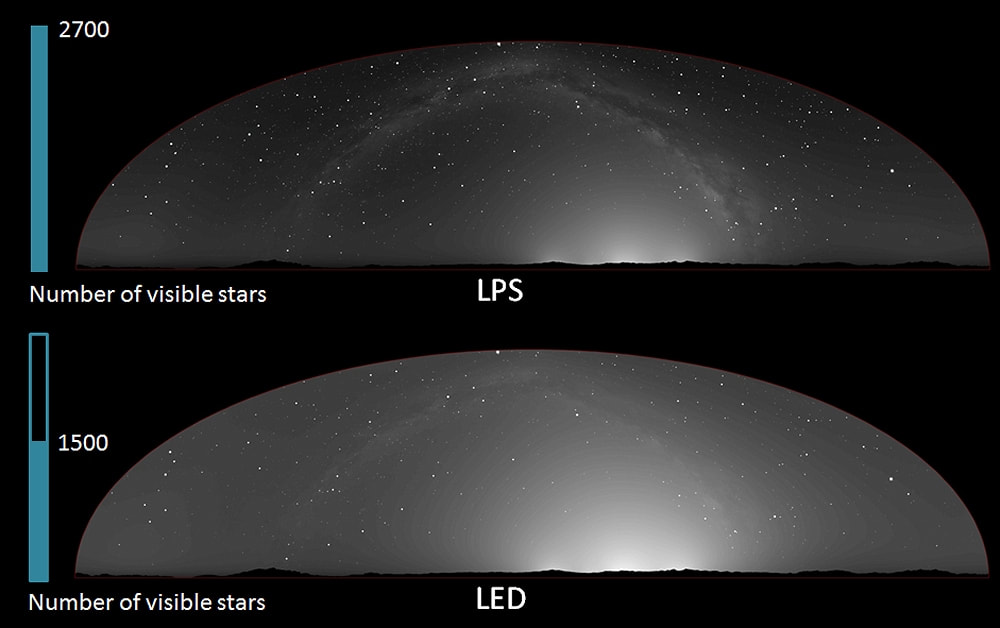

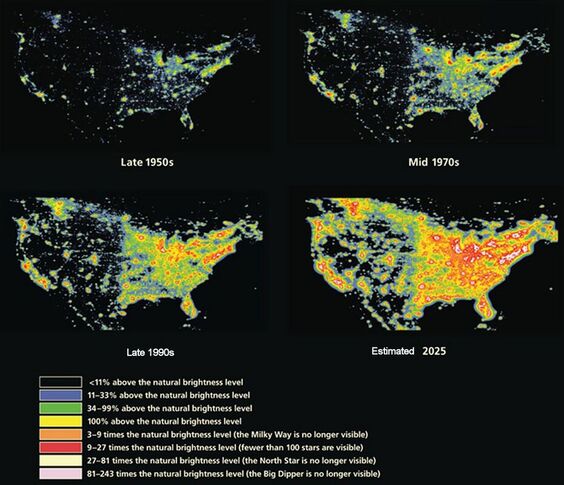

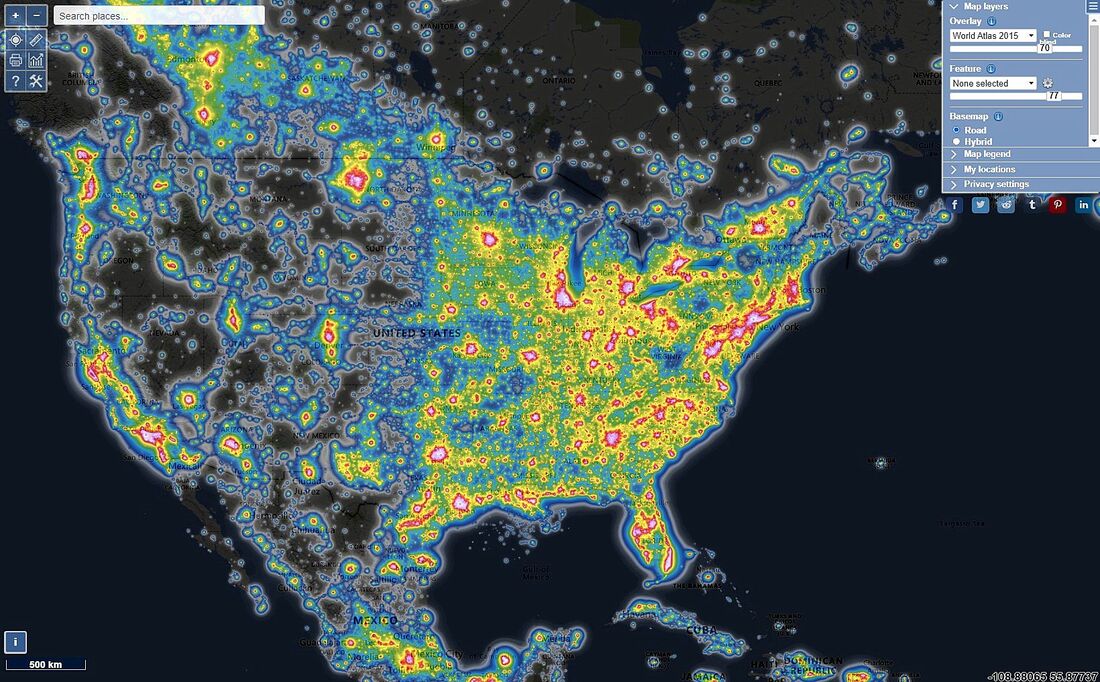

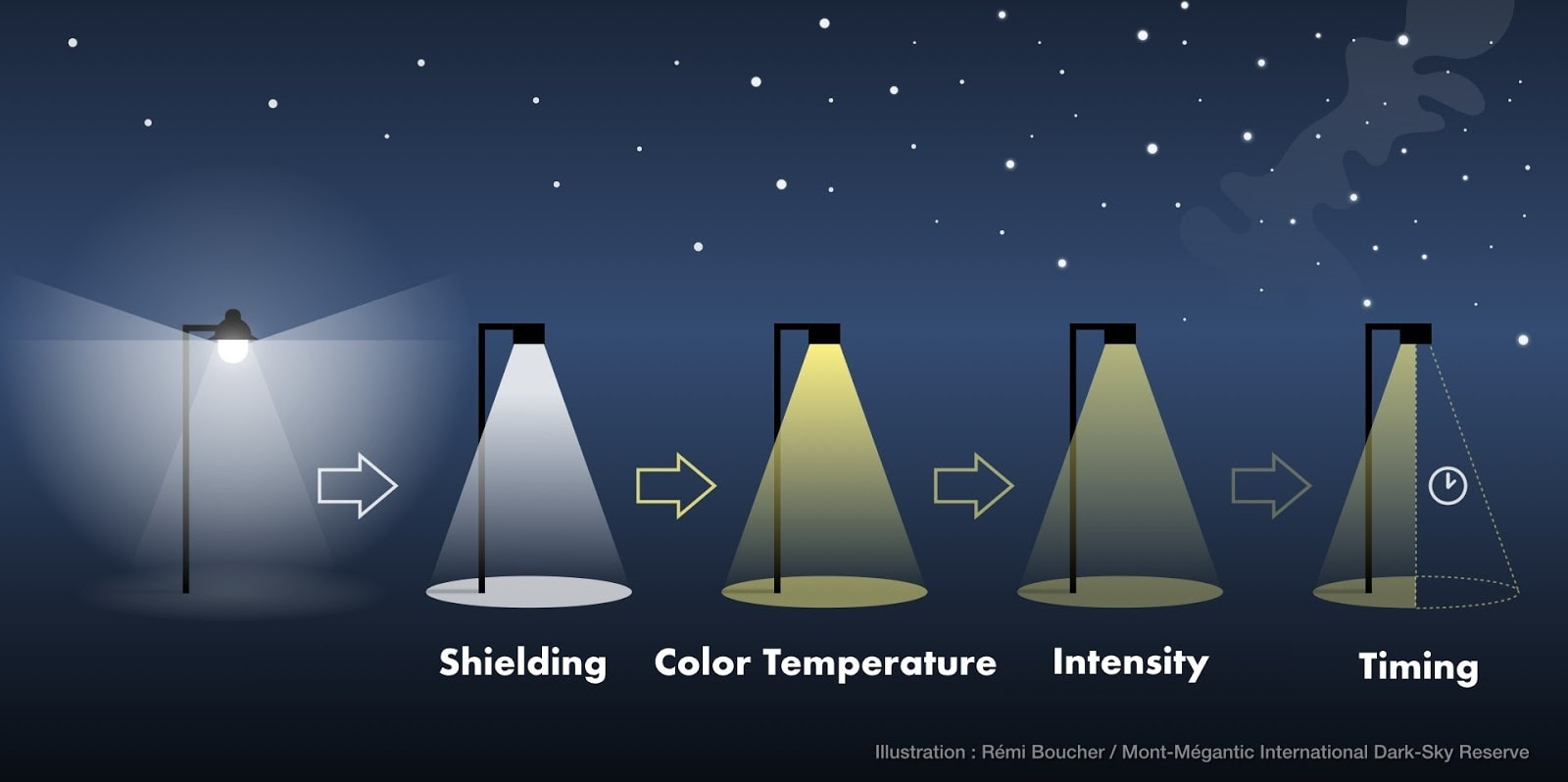

Light pollution is doubling every eight years. For more than a century, most sources of artificial light wasted energy in the form of heat. LEDs are much more efficient, requiring less than 25% of the energy consumed by an incandescent lamp. By 2020, LEDs accounted for 51% of global lighting sales, up from just 1% in 2010, according to the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization that analyzes global energy data. It sounds like a clear win for the environment. But that's not how Ruskin Hartley sees it. "The drive for efficient fixtures has come at the expense of a rapid increase in light pollution," he said. Hartley would know. He's the executive director of the International Dark-Sky Association, or IDA, and he's one of a growing number of people who say the dark sky is an undervalued and underappreciated natural resource. Its loss has detrimental consequences for wildlife and human health. And yet the public's embrace of LEDs keeps rising, spilling way too much light into the sky where no one needs it. "We've taken a lot of the energy savings and just lit additional places," Hartley said. It's a classic example of the Jevons paradox, in which efficiency gains (such as better automobile gas mileage) are countered by an increase in consumption (people driving more often). In essence, Hartley and others say, we've traded one kind of pollution for another. That's not the only problem. In addition to making more light, LEDs have altered its fundamental nature. The light produced by incandescent bulbs had warmer amber or yellow colors, "more in tune with firelight, the only light aside from starlight we knew," said Robert Meadows, a scientist with the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division of the National Park Service. LEDs, in contrast, give off cooler bluish-white tones that exacerbate light pollution for the same reason that the sky is blue. Sunlight contains the full spectrum of colors, and air molecules happen to be the right size to scatter the shorter blue wavelengths more effectively than any other. This causes blue light to spread more readily in the atmosphere, giving the daytime sky its familiar color. After the sun goes down, the same thing happens with LED light that spills wastefully into the sky: It gets diffused to a greater extent and increases "sky glow," the combined radiance of city lights. Travis Longcore, an urban ecologist at UCLA, estimates that artificial lighting causes the night sky in Los Angeles to shine 1 1/2 times brighter than a night lit by a full moon. All creatures are affected by the brighter nightscapes, especially those who cannot close the blinds for a sound sleep. "There are many, many species who don't go out and forage during the full moon because it's too bright and they know they're going to be vulnerable to predators," he said. According to the National Audubon Society, 80% of North American migratory bird species fly at night, and they're confounded by city lights. Even species that stay put are forced to relocate their homes. A recent study led by Longcore found that Western snowy plovers, a threatened species of shorebird, look for safe roost sites in darker areas of Santa Monica Bay when mostly empty parking lots are illuminated with floodlights all night long. The survival of wild species depends on the variabilities of the natural world—day and night, seasons, the lunar cycle. Take them away, Longcore said, and you inevitably start alienating species from their natural habitats. Snakes, for example, are most active and hunt prey during new moon nights. The disappearance of the California glossy snake and the long-nosed snake from Orange County has been attributed largely to the increase in ambient light. Humans, too, are vulnerable to light pollution. Artificial light blocks the production of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep cycles, and disrupted sleep cycles have been linked to an array of health problems. The American Medical Association warned in 2016 that high-intensity, blue-rich LED lights were "associated with reduced sleep times, dissatisfaction with sleep quality, excessive sleepiness, impaired daytime functioning, and obesity." A new study published in Science reports that between 2011 and 2022, global sky brightness increased by an estimated 9.6% per year. The study is based upon data collected through the community science project, NOIRLab’s Globe at Night. This rapid brightening of the night sky over large portions of the Earth has serious consequences for all living things. The authors conclude that “existing lighting policies are not preventing this increase, at least on continental and global scales.” The startling increase in light pollution is a clear wake-up call for policymakers that decisive and immediate action is needed to address this urgent environmental threat. Why is this finding surprising? In the past few years, studies have estimated that light pollution was growing by approximately two percent per year. These studies use data from earth observation satellites. In other words, they measure the light escaping the atmosphere. The new study, reported in Science, relies on people recording the number of stars they see on a clear, dark night. In other words, they assess night sky brightness from the ground looking up. These observations measure skyglow, the brightening of the night sky from countless lights. The satellites primarily measure light emitted vertically, either directly or via reflection. They are also blind to light in the bluer, short wavelength. The observations of the night sky from the ground also include light emitted horizontally – such as lit building facades, digital billboards, and light escaping windows. Additionally, the human eye sees the light across a broader spectrum. These observational factors are more causative of skyglow and useful predictors of biological impact. “Since human eyes are more sensitive to these shorter wavelengths at nighttime, LED lights have a strong effect on our perception of sky brightness,” said Christopher Kyba, a researcher at the German Research Centre for Geosciences and lead author of the paper detailing these results. “This could be one of the reasons behind the discrepancy between satellite measurements and the sky conditions reported by Globe at Night participants.” Why do the results matter? Over the past 150 years, we have transformed the natural world. It is becoming increasingly clear that one of the most profound changes is the loss of darkness at night over much of the planet. As the study authors report, “the character of the night sky is now different from what it was when life and civilization developed.” It is clear from this paper that the growth of light pollution is continuing, largely unchecked. “At this rate of change, a child born in a location where 250 stars were visible would be able to see only about 100 by the time they turned 18,” said Kyba. Increasing sky brightness is a sign we are doing lighting wrong. It’s a sign we are using energy inefficiently, wasting money, exacerbating climate change, and increasing environmental impacts. Scientists estimated that carbon dioxide, the primary contributor to climate change, is growing at 2% per year globally – doubling every 30 years. By comparison, light pollution is growing at 9.6% per year – doubling in less than eight years. “The increase in skyglow over the past decade underscores the importance of redoubling our efforts and developing new strategies to protect dark skies,” said Connie Walker of the National Science Foundation's NORILab. “The Globe at Night dataset is indispensable in our ongoing evaluation of changes in skyglow, and we encourage everyone who can to get involved to help protect the starry night sky.” How was the study conducted? Thousands of volunteers collect data on how many stars they can see yearly. Using a simple phone app, they compared the number of stars they saw in a well-known constellation to estimate the level of light pollution. Using more than 50,000 data points collected between 2011 and 2022, the scientists compared the data collected to a sky brightness model. The model estimated that globally, light pollution has been growing at 9.6% per year every year. What are the implications of this study? As noted in the main study, existing lighting policies have failed to prevent these increases, at least at a continental or global scale. In a companion Perspectives piece in Science, authors Fabio Falchi and Salvador Bara call for a new approach to slow, halt, and reverse this alarming trend. They conclude, “light pollution is an environmental problem and should be confronted and solved.” New approaches could include establishing regional lighting budgets and limits based on sky quality over parks, protected areas, and astronomical sites. In other words, taking a similar approach to how we regulate and control air and water pollution. This is consistent with the approach we called for in our European policy brief released to support the Brno appeal to reduce light pollution in Europe. Unlike many other forms of pollution, we can reduce light pollution using existing technology. Once addressed, the results are immediate, and the cost savings, in terms of ongoing energy savings, are significant. Critically, it does not mean turning off all the lights. By following the Five Principles for Responsible Lighting, we can take immediate steps to reduce light pollution while enhancing light quality at night.

How can I help?

Sourced from the Los Angeles Times and darksky.org |

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Donations to Dark Sky Defenders do not go to DarkSky International. Please contribute directly to DSI for donations and memberships.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed