|

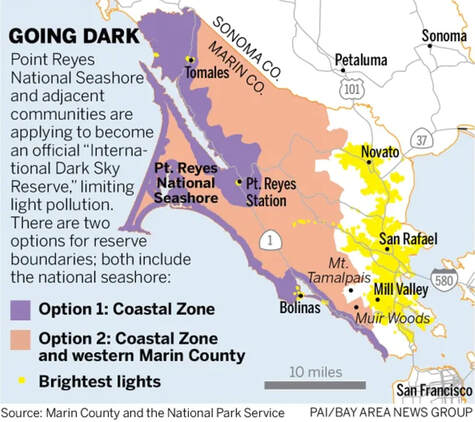

Bulb by bulb, this Bay Area outpost is preserving its dark sky in a quest to join an exclusive club Point Reyes aims to become an official Dark Sky Reserve, limiting lights in California’s popular coastal playground. Lisa M. Krieger, San Jose Mercury News Mobilizing to preserve a celestial view under threat from the Bay Area’s growing glow, the community has applied to become an official International Dark Sky Reserve – a cherished status shared by fewer than two dozen places on Earth. But going dark is easier said than done, because the light problem is everywhere: in the school that educates rural children, in the restaurants that define California cooking, in the ranches that raise famed grass-fed beef, in the firehouse that protects against a flammable landscape. “Dark skies are important,” said Sheryl Cahill, who plans to spend thousands of dollars to install downward-facing lights at her two popular restaurants, the Station House Cafe and Side Street Kitchen. “But so is safety and the ability to navigate the town.” To gaze at the West Marin sky is to see sights hidden to the rest of the Bay Area. If your back is turned to the horizon’s glare of Highway 101, it’s possible to view 2,000 stars. Want to stay out all night? As the Earth rotates, the number soars to 6,000. On a recent moonless night, stars glittered like scattered diamonds. “It’s absolutely beautiful – and our whole basis of time and place,” said local astronomer Don Jolley at a recent stargazing event, part of the movement’s effort to boost public awareness. The crowd, wrapped in warm blankets in a circle of lawn chairs and hot drinks, stared up at the inky blackness. There’s a trio of faint but perfect pairs: Talitha, Tania and Alula. Ancient Arabs described them as the three leaps of a gazelle, startled at the waterhole by the nearby constellation of Leo the Lion. Nearby is a delicate glow, representing Cancer the Crab, the dimmest of the 13 signs of the Zodiac. In the same neighborhood as the red star of Regulus and showy Gemini Twins, it could be easily missed. There’s the soft spectacle of the Andromeda galaxy, 2.5 million light-years away and the most distant thing visible to the unaided eye. Squinting, you can make out a cluster of young stars dubbed the “Beehive.” The Old Testament says that these bees swarmed out of the skull of a lion slain by warrior Samson – recounted in song by Marin’s own Grateful Dead. “These newly born stars are coming alive and lighting up the remnants of gas and dust out of which they were born,” Jolley told the rapt crowd. “It’s a nursery.” This display is what makes the region such a strong candidate for official Reserve designation, said Ashley Wilson of the Arizona-based International Dark Sky Association, a group that promotes awareness of light pollution. A reserve must comprise at least 173,000 acres and is much larger than the more common Dark Sky Place. The only other U.S. site in Idaho, stretching from Ketchum to Stanley; required nearly two decades of work and policy decisions. Other applications are underway in Colorado and Texas. Bulb-by-bulb analysis begins The process is rigorous, requiring data collection, community education and adoption of light-limiting features, such as timers, dimmers, motion sensors, softer and warmer LED bulbs and shields, so that light shines only where it’s needed. Only about 20% of initial queries make it through to completion, Wilson said. The West Marin effort was initiated by the Point Reyes Village Association, the town’s governing body, but has since been taken over by the National Park Service. “I think there is a really interesting opportunity here because Point Reyes still maintains good night sky quality and is so close to the metropolitan areas of San Francisco and Oakland,” Wilson said. The core of the reserve would be the Point Reyes National Seashore, its unblemished heavens on the edge of the vast Pacific. The periphery could include the brighter and busier West Marin villages of Point Reyes Station, Inverness, Olema, Marshall and more. Because conversations with communities have just started, there are no boundaries yet. For decades, population growth and development in the Bay Area have crept closer to this landscape, bringing more glare and glow. The rise of light pollution has accelerated in recent years with the widespread adoption of powerful LED lights. Night skies have never gained the protection offered air, land and water. While still an outpost, the region is one of California’s most popular playgrounds, attracting about 2.7 million visitors a year to its trails, beaches, oyster bars, bakeries, restaurants, bookstore and a feed barn that serves organic pastries and coffee. This makes it hard to banish brightness. Where to even begin? Bulb by bulb, the Park Service is measuring 1,000 different spots – from its Bear Valley headquarters and staff residences to a hostel, riding stable and 30 ranches – with a $3,000 handheld spectrometer. On the windswept edge of Drakes Estero, the 800-acre D. Rogers Ranch has installed modern motion-sensing lights, activated only when needed, around its historic white-washed barns, said fourth-generation rancher David Evans. ”I support and enjoy a dark night landscape, closer and more shared proximity to nocturnal wildlife, and the beauty of a more visible Milky Way,” said Evans, who supplies organic grass-fed beef to Marin Sun Farms and Mindful Meats. But in town, there are far greater challenges. At some sites, such as a PG&E substation, there’s no local control. “Everybody, in principle, would be for such a move,” said Frank Borodic of the West Marin Chamber of Commerce and owner of Olema’s bucolic Inn at Roundstone Farm. “But it’s a complex issue that would require some effort and strategic planning.” It is costly to replace fixtures, he said. There aren’t easy substitutes for many lights. With more transients in town, businesses have security concerns. It could also be unsafe if a visitor trips and falls. “We don’t have normal sidewalks around here,” said Cahill, who was legally liable when an elderly woman fell in her dark parking lot 16 years ago. Walking in the dark between her businesses, “I really don’t want to twist my ankle.”  Lights glow at the Fire Station in Point Reyes Station, Calif., as night falls, Wednesday, Feb. 23, 2022. The nearby Point Reyes National Seashore is applying to earn official designation as International Dark Sky Reserve, one of just two dozen such reserves worldwide, but some area buildings may need to alter their outdoor lighting. (Karl Mondon/Bay Area News Group) Light conservation underway Small changes are already underway. Later this year, Point Reyes Station’s illuminated clock will come down. Some streetlights have shields. The fire station’s renovation will add sensors and off switches. The hardware store has pledged an aisle to light-conserving fixtures. But the town’s only bank is bathed in brightness; while it put up a shield on one light, corporate management wants to protect its ATM and parking lot. The beloved Palace Market, the town’s sole grocery, remains luminous. West Marin School, the site of several recent break-ins, has turned off its brightest spotlights after 9 p.m. But for surveillance, the parking lot is still lit. Lights also help protect the town’s quaint public safety station, a welcoming but vulnerable place where anyone can stop by for a visit, said Ben Ghisletta, the fire station’s senior captain. The rear parking area is not fenced, leaving officers unprotected. In a fire or medical emergency, rigs rush out at a moment’s notice, so risk hitting pedestrians they can’t see. But darkness is a lifestyle pledge being shared by more and more local residents in an ever-brighter world, said county Supervisor Dennis Rodoni, who represents the region. The county will draft an ordinance that adopts the initiative, he said. If implemented, it could lead to phased-in future building and design codes that are more restrictive than existing light-limiting rules. “It’s just step by step. I’m pretty optimistic,” he said. ”It demonstrates the commitment to the environment by the West Marin villages and their sensitivity to the impact of our footprint.” If successful, safe and secure, a Dark Sky Reserve designation would add another layer of protection in a place once destined to be just another suburb. “We want everybody to see what we see,” said resident Peggy Day, who helped launch the effort. “If we get this, we can save this beautiful skyscape for all future generations.” Lisa M. Krieger is a science writer at The Mercury News, covering research, scientific policy and environmental news from Stanford University, the University of California, NASA-Ames, U.S. Geological Survey and other Bay Area-based research facilities. She graduated from Duke University with a B.A. degree in biology. She splits her time between Palo Alto and Inverness, and in her spare time likes wildlife photography, swimming, skiing and backpacking. |

Archives

July 2024

|

|

Donations to Dark Sky Defenders do not go to DarkSky International. Please contribute directly to DSI for donations and memberships.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed